External Anatomy of Ants

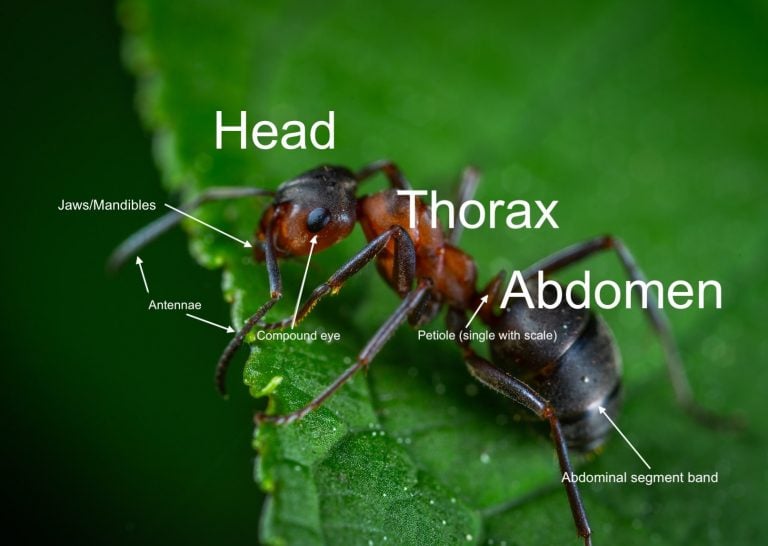

There are three main body parts of an ant with six legs and two antennae. Yet the external anatomy of ants is far more than this.

Here I discuss the external anatomy of ants or the body parts of an ant. As with all insects, ants have their skeleton on the outside, though it’s not quite like the skeleton we think of, such as the one we have inside of us. The ant’s skeleton has many layers, just our skin, and offers the ant four things;

Hard-protective armour covering

Strong base for muscle attachment

Filter of dangerous solar rays

Prevents dehydration

The ant’s body, or external anatomy, consists of three segments:

Head

Thorax

Abdomen (including a one or two segmented petiole).

External Anatomy of Ants

The Head

The Jaws

An ant’s head has on the outside of it, the jaws (or mandibles), the mouth, the antennae and the eyes.

The ant uses its jaws, or mandibles, to pick objects up. They are hollow and tough. However, the jaws are gentle enough to carry the delicate brood..

Ants use their jaws to get ahold of prey in order to sting, spray with acid, or simply tear apart. They also use them as a means of attack and defensive when fighting, for example, invading ants.

The ants use their mandibles as the main tool in the construction of new chambers and tunnels in their nests.

Some tribes in Africa also use the jaws of an ant as a method to close wounds on people; the grip is that strong. The jaws usually have little teeth on them, being larger at the front of the jaw and smaller at the back. This helps the ant grip objects and prey. Their jaws can close with such force that some species of ant, such as the soldier of the Leafcutter, can cut through leather. They are strong enough to puncture the bodies of their prey/enemies yet gentle enough to tenderly pick up their brood (‘babies’). Much like the teeth of a cat that can tear meat from bones, yet gentle enough to carry kittens about in their mouths.

The Mouth

The ant’s tongue does not have muscles to move it as we humans do, but rather it uses blood pressure to cause the tongue to project out of its mouth. When an ant drinks water, it doesn’t lap it like a cat but places its tongue on the liquid. The water then travels up the tongue, into the mouth, and down into its digestive tract. Ants also use their tongue to clean their brood, queen and each other. Some believe that the ant’s saliva contains an anti-microbial substance.

Like a cat’s tongue, the tongue of the ant has rough striations on it. That’s what makes a cat’s tongue feel rough when it licks you. The ant also uses its tongue to wash itself, in a similar way to that of the cat. The cat licks its paw and then wipes that paw over its head, whereas an ant does the same, only in reverse. The ant rubs its legs over its body and then transfer the dirt to its front legs. She then passes its front leg over her mouth, where the dirt is captured into a little pocket, called the infra-buccal pocket, just below the mouth. Once this pocket is full the ant empties it into a rubbish pile usually outside of the nest.

The Eyes

The Eyes are compound in structure, meaning that they are made up of many individual lenses, like that of a fly. Different species of ant have different numbers of lenses (or ommatidia to give them their proper name). For example, the yellow meadow ant Lasius flavus have 45 ommatidia per eye, whereas in Formica cunicularia there are 460. In Lasius niger, 120, and in some army ants, only one. As mentioned above, ants generally have poor eyesight, but some can make out landmarks and detect movement. I kept a colony of Formica fusca some years ago. They seemed to have good eyesight for ants as they would see me approaching their tank from across the room. I observed them dashing for cover when I entered the room on many occasions.

Flying ants have three light sensitive cells on the top of their heads which, it is believed, assist in navigation when flying.

The Antennae

The antennae are perhaps the most important sensory organ that the ant possesses. They act as the ant’s sense of sight, hearing and taste. It might seem odd to say that the antennae act as eyes when in fact the ant already has eyes, but the eyes of ants are generally not that good at seeing. Ant eyes can detect light, particularly ultraviolet light, but as you can probably imagine when underground the ant’s eyes see nothing at all. Instead the ants rely on their antennae to act as their primary sense of seeing and hearing.

Ants can detect chemicals in the air and scent trails on the ground. They are also sensitive to air pressure changes and vibrations. The antennae are hinged roughly about halfway down their length, which is one of the identifying features of ants. They are very mobile, being able to sweep through the air or come together to feel something on the ground that is less than one millimetre in size.

When an ant gets into a dangerous situation, such as attacking prey or enemy ants, the antennae can be folded back across the head to protect them.

External Anatomy of Ants

The Thorax

The middle section of the body parts of an ant is the thorax, or, mesoma, from which the six legs emerge. In worker ants, it is a rigid, complete fixture, though it does have fused segments within it. In the worker, it is normally more slender than the head of the ant, whereas the queen it is much wider than the head.

Thorax segments in the queen ant are flexible, which helps the use of the wing muscles. Spiracles are tiny inward-facing tubes through which air enters the ant’s body, much like our trachea, from the thorax, though the ant does not have lungs with which to inhale and exhale the air.

The thorax also has two ducts from which a greasy substance is produced which is used to keep the ant clean from infection. It is also believed to be part of the source of the ant’s colony scent, which helps ants distinguish nest mates from enemy ants.

The thorax sometimes has, depending on species, backward facing spines on the rear edge. This are used to help protect the ant’s body. They are known as epinotal spines. Myrmica rubra have these spines, for example.

The Wings

Found only on males and unfertilised queens are the wings, of which each has two pairs. These wings come into play during the mating season, when males and unfertilised queens will take to the air in order to look for a mate. After mating, the queen removes her wings using her legs to unhook them from her thorax. The queen has no need of wings.

The Legs

The ant’s leg has five main joints. The outermost end is further sub-divided to make the foot, which ends in two curved claws and is superbly adapted for movement over uneven ground.

The front legs have fine hairs on them that act as a comb as a means of cleaning itself. The rear most legs are the longest and allow the ant to lift itself clear off the ground. This enables her to bring her abdomen underneath herself, bringing the sting forward. The queen can do the same when laying eggs.

Ant legs have fine hairs and sensory organs on and within them, that give the ant input about its orientation to the ground. The ant knows whether it is on flat ground, on a wall face, or even walking upside down.

There are sticky pad between the claws on their feet, which enables them to climb (and cling upside down) to smooth surfaces, such as glass.

External Anatomy of Ants

The Abdomen

The final section of the external anatomy of ants is the abdomen. It consists of a series of plates connected by elastic tissue. The plates tuck in under one another along their leading edge. When the ant’s stomach is full, or when the queen is ready to lay a lot of eggs, these plates can stretch apart. The underling elastic connective layer can then be visible as pale bands.

The Sting

The abdomen also contains the sting, but this is dependant on species. Not all species of ant possess a sting. The ant inserts the sting into the skin of its prey, or enemy provided the ant can get a good grip with its jaws. When stinging an insect, such as another ant, the attacking ant probes her victim’s cuticle with her sting. If she manages to find a gap in the hard exoskeleton, she will insert the sting into its body. Ant stings are smooth; not barbed as the honeybee’s sting is.

Queen ants, of the stinging species, also have stings that they can use to defend themselves or their brood. Male ants do not possess a sting in any species.

The Petiole

This is a peculiarity of the insect world, found in ants, bees and wasps. It is located between the thorax and abdomen. It consists of one or two segments of the abdomen narrowed into a thin tube like structure. In the Myrmicinae sub-family of ant species, there are two of these petiole segments. In all other ants there is only one. The petiole allows the ant to bring its abdomen from underneath itself as described earlier.

In Myrmicinae ants the second petiole segment can be rubbed against a series of very fine ridges, located on the back edge of the abdomen. When this is done it produces a high pitched squeaking sound. This sound can just about be heard if you hold the ant to your ear. You will need to gently hold the ant by its thorax so that its abdomen is free to move about. If you have good hearing you may be able to hear the sound it makes, though it is barely audible. It is believed that this sound is used to shock predators into dropping the ant. Others have also suggested that the sound may attract nest mates if the ant is trapped, say for example, following a tunnel collapse.

Formicine ants, such as Lasius niger, have a scale on their single petiole.

External Anatomy of Ants

Internal Anatomy of the Ant

If you enjoyed reading about the external anatomy of the ant, why not pop to the next page and read up on the internal anatomy the ant. Click on the button below.

Ask questions about ants

If you wish to ask me a question about ants (and no, I won’t tell you how to destroy them or their nests!) then please contact me on my**@an*****.uk or you can ask on the contact thread

I aim to respond to your questions as quickly as I can, normally within 24 hours.